This is a brief draft from my dissertation chapter on the history of public Montessori. Comments welcome! MD

Alongside the immediate popularity of the Montessori method in America in the early 1910s as a form of private schooling for those who could afford to pay for it, there were several examples in the early teens of Montessori programs in public schools or serving disadvantaged students in the public and private sector. The first examples of publicly funded Montessori classrooms were in institutes for the deaf starting in 1912, Torresdale House in Philadelphia and the New York Institute of the Deaf, and then the Rhode Island Institute of the Deaf in 1913 (Commissioner of Education 1914). The first public Montessori classrooms in traditional elementary schools were established in 1913 in Los Angeles and Providence, Rhode Island. Katherine Moore, who trained with Maria Montessori in Rome, established two classrooms at two separate Los Angeles elementary schools, one entirely outdoors, for foreign-born students, and one for American born students (Los Angeles Times 1913). In Rhode Island, Clara Craig, who had been funded by the Rhode Island State Board of Education to take the Montessori training course in Rome, established a Montessori classroom in 1913 at the State Normal School, a teacher’s college in Providence (Rhode Island Board of Education 1918). Four years into the experiment, Craig reported to the State Board of Education:

These children, even now, excel, by far, the prescribed attainment of children who have progressed beyond regular first grade work. They are attracting the curious interest of expert educators. It is to be deplored that our American adaptation of the Montessori method of child culture cannot be extended on account of our present condition of space limitations. It is the opinion of scrutinizers that an enlargement of this particular work would carry a benefit beyond the schools of our own state. (Craig 1918: A25-26)

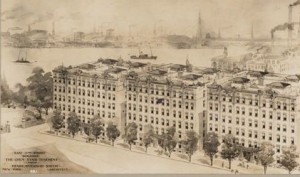

Other early experiments created privately funded classrooms for poor students. In New York, Montessori classrooms were set up in the Vanderbuilt funded John Jay Dwellings on New York’s then unglamorous upper-east side (Whitescarver and Cossentino 2007; Kramer 1978; New York Times 1915a). Elite New Yorkers held a Ma-Careme Ball at the Plaza Hotel to raise funds for the Montessori Tenement Schools of New York (New York Times 1915a) where moving pictures of the children were shown alongside booths selling carnival favors including “grotesque noses, paper headgear…toy balloons” (New York Times 1915b).

Organizers of Montessori’s famous glass classroom, part of the 1912 San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition deliberately selected for economic diversity: the 21 children selected out of 2000 applicants including children from humble homes as well as the children of San Francisco elite, including the three year old daughter of General John Pershing, who tragically died in a house fire as the exposition was underway (Kramer 1978).

This flurry of Montessori in the public sector and for impoverished students was ephemeral and declined as the Montessori movement dropped out of public favor by 1916[1] due to a split between Montessori and her American adherents and external critiques. First, as Montessori began to codify her movement (and also left academia and relied on teaching courses and selling materials for her income), she became more intellectually proprietary, ultimately choosing to retain control over her method at the cost of its free expansion in the United States (Kramer 1976/1988). This proprietary concern led to conflicts with her earlier supporters, the dissolution of the Montessori Education Association in 1917 and the suspension of all American training courses. After 1918, Maria Montessori never returned to America. Finally, prominent critiques from leading American educators like Columbia Teacher’s College professor William Heard Kilpatrick disparaged Montessori for being derivative of other methods, creating a cult, “unscientific,” though granting freedom, restricting children’s free expression (Kilpatrick 1914). These critiques and others that followed led her method to fall out of favor in established education research and pedagogical circles. As a result, Montessori education largely died out in America in the period from the 1920s to the early 1950s.

[1] Clues about the duration of the programs are hard to uncover as openings of new programs are often newsworthy, but their closures are less so. At least one program, the Rhode Island Institute of the Deaf’s Montessori classroom, was still going in 1922 (Rhode Island Board of Education 1922)

Works Cited

Commissioner of Education. 1914. “Annual Report.” Vol. 2. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved August 18, 2015. (https://books.google.com/books?id=7q40AQAAMAAJ&printsec).

Craig, Clara. 1918. “Rhode Island Normal School.” Edited by Rhode Island Board of Education. Albany, NY: Hamilton Press. Retrieved August 18, 2015. (https://books.google.com/books?id=NhFFAQAAMAAJ&printsec).

Kilpatrick, William Heard. 1914. “Montessori System Examined.” New York: Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved August 18, 2015. (https://books.google.com/books?id=n7VKAAAAYAAJ&dq).

Kramer, Rita. 1976/1988. Maria Montessori: A Biography. New York: Da Capo Press.

Los Angeles Times. 1913. “Children Their Own Educators.” Sep 15, p. I11 (http://search.proquest.com/docview/159995112?accountid=15172).

New York Times. 1915a. “Mi-Careme Gayety Lure for Society.” Pp. 11 in New York Times. New York: Proquest Historical Newspapers.

New York Times. 1915b. “Benefit Ball for Montessori Schools.” Pp. 7 in New York Times. New York: Proquest Historical Newspapers.

Rhode Island Board of Education. 1918. “Annual Report of the Board of Education Together with the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Public Schools.” Albany, NY: Hamilton Press. Retrieved August 18, 2015. (https://books.google.com/books?id=NhFFAQAAMAAJ&printsec).

Rhode Island Board of Education. 1922. “Annual Report of the Board of Education Together with the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Public Schools.” Providence, RI: EL Freeman Company. Retrieved August 18, 2015. (https://books.google.com/books?id=YRFFAQAAMAAJ&printsec).

Unidentified Artist ed. 1911. Open Stair Tenement Co.: John Jay Dwellings: East 77th Street Buildings. New York: The Open Stair Tenement Company, Henry Atterbury Smith Architect.

Whitescarver, Keith and Jacqueline Cossentino. 2007. “Honoring the Past: Montessori and the Public Good.” Paper presented at the AMI/USA Public Montessori Conference, November 2-4, Hartford, CT.

Whitescarver, Keith and Jacqueline Cossentino. 2008. “Montessori and the Mainstream: A Century of Reform on the Margins.” The Teachers College Record 110(12):2571-600.